January's Case of the Month-2024

A Twist of Events

Patient Information:

Age: ~4 years

Gender: Spayed Female

Species: Canine

Breed: English Bulldog

History:

Patient presented for lethargy, inappetence, and hematuria of a few days duration. Patient was pale upon presentation with firm organomegaly of the cranial abdomen on palpation. CBC showed anemia with a leukocytosis and hypoalbuminemia. Radiographs showed severe organomegaly cranial abdomen. A slide autoagglutination test was run and appeared positive. Patient was started on prednisone 30 mg SID and Clavamox 250 mg BID. Urinalysis show a possible infection as well.

Ultrasound Findings:

Liver: Mildly decreased in size, normal shape and echogenicity. No focal lesions are appreciated. The gall bladder is moderately distended with normal anechoic and hyperechoic unorganized dependent bile that is not resulting in obstruction. No common bile duct dilation is seen.

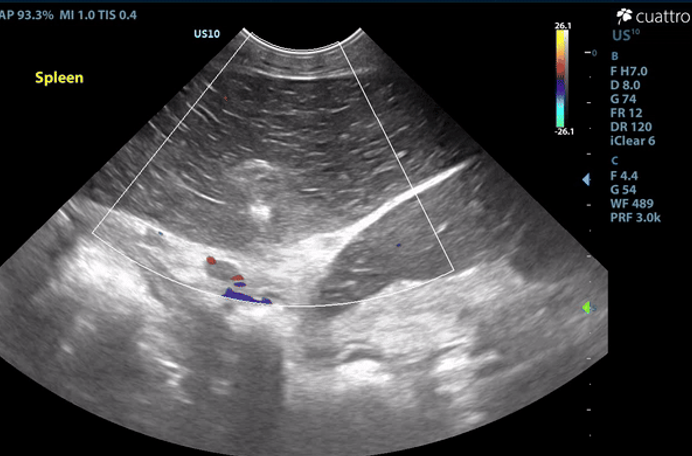

Spleen: The spleen measures 2.9 cm in depth and rounded in shape. There is diffuse hypoechoic echogenicity with hyperechoic linear striations creating a lacy echotexture. There is no appreciable blood flow noted throughout the splenic parenchyma with color flow doppler. The mesentery surrounding the spleen is moderately hyperechoic.

Image 1: Absent color flow doppler signal throughout the splenic parenchyma and vasculature. The spleen is diffusely hypoechoic with hypechoic linear striations producing a lacy echotexture.

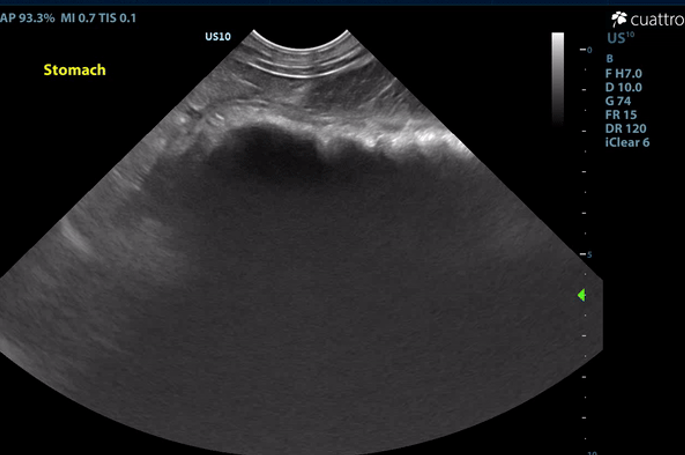

Intestinal Tract: The stomach contains a moderate amount of amorphous ingesta as well as amorphous,hyperechoic material associated with a strong anechoic shadow measuring ~7.8 cm in length. The stomach has normal visible wall thickness and layering. The pylorus is free of obstruction. Most loops of small intestine visualized have increased wall thickness measuring up to 6.0 mm with disproportionately large mucosal layers having hyperechoic radiating striations consistent with lymphangiectasia as well as echogenic stippling throughout. The bowel has increased overall motility and liquid contents.

No obstruction or masses seen. The colon has normal wall thickness and layering throughout.

Maximum thickness measurements: Stomach- 4.7mm; Duodenum- 2.8mm; Jejunum-6.0mm; Colon- 1.1 mm

Image 2: Hyperechoic material within the stomach creating a strong anechoic shadow.

Image 3: Linear striations diffusely throughout the mucosal layer of the jejunum consistent with dilated lacteals.

Serosal Surfaces: A mild amount of anechoic free fluid was noted throughout the abdomen. There is moderately hyperechoic mesenteric echogenicity. No focal lesions noted.

Abdominal Ultrasound Interpretation:

Spleen - the findings are severe - DDX: splenic torsion vs. infarct vs. infiltrative neoplasia vs open.

Intestines - the findings are moderate - DDx: protein-losing enteropathy (lymphangiectasia), lymphosarcoma, severe inflammatory bowel disease, histoplasmosis, lipogranulomatous lymphangitis). Rule-out protein-losing nephropathy (nephrotic syndrome) as source of protein loss.

Causes of Protein-Losing-Enteropathy (PLE)

A. Diseases affecting intestinal lymphatic drainage

Primary lymphangiectasia

Congenital or idiopathic acquired

Breed predisposition (including Yorkshire Terrier, Soft-coated Wheaten Terrier, Basenji, Norwegian Lundehund, and Chinese Shar-pei)

Secondary lymphangiectasia

IBD

Heterobilharzia americana

Neoplasia

Congestion secondary to right-sided heart failure or portal hypertension

B. Acute or chronic inflammatory diseases that result in increased mucosal permeability to protein

Inflammatory bowel disease (eosinophilic or lymphoplasmacytic enteritis)

Granulomatous enteritis (histoplasmosis, Pythiosis)

Intestinal neoplasia, (lymphoma, carcinoma)

Immunoproliferative enteropathy of Basenjis

Parasitic enteritis in young animals

Villous atrophy, gluten enteropathy, certain viral and bacterial enteritides

Chronic obstruction or intussusception

C. Gastrointestinal Blood Loss

Bleeding tumors

Ulceration/erosion

Intestinal parasites (Hookworms)

Gastric Foreign Body - the findings are moderate and suggestive of an intraluminal gastric foreign body vs. recently ingested bone/chew/etc. vs. open

Microhepatica (decreased hepatic mass) The findings are mild - DDX: Chronic hepatic disease with progressive loss of hepatocytes (cirrhosis or pre-cirrhosis) Decreased portal blood flow with hepatocellular atrophy

Congenital portosystemic shunt

Intrahepatic portal vein hypoplasia (presumptive diagnosis - biopsy confirmation is necessary)

Chronic portal vein thrombosis

Hypovolemia

Hypoadrenocorticism

Ascites - this finding is mild - DDx: transudate vs. hemorrhagic vs. exudate

Mesentery - the findings are moderate - DDx: peritonitis - inflammation vs. paraneoplastic reaction vs. infectious vs. fibrosis vs. other.

Recommendations:

The splenic appearance and lack of color flow doppler signal is consistent with a splenic torsion or infarct. Exploratory laparotomy is recommended for splenectomy and histopathology.

The ingesta within the stomach is associated with strong anechoic shadow which can be consistent with foreign material. Exploratory laparotomy is recommended for further evaluation of the intestinal tract and gastrotomy if indicated. The changes to the small intestinal tract are consistent with dilated lacteals, a common finding seen in dogs with a protein-losing enteropathy (PLE). Given the reported hypoalbuminemia (1.5 g/dL), PLE would be a primary differential in this patient. If surgery elected, GI biopsies are recommended to better define the nature of the disease present. Consider submitting a Texas A&M GI panel and switching to a strict novel protein diet if not already done.

The cause of Rogue's anemia (HCT 15%) is not definitively identified in this study. While anemia is a common comorbidity associated with splenic torsion, further investigation is necessary to assess the true etiology, especially in light a positive slide agglutination test. A CBC with pathology review is recommended to assess for regenerative changes, red blood cell morphologies, red blood cell pathogens, etc. A tick PCR panel should also be considered to assess for inciting causes of immune mediated anemia.

Abdominocentesis of the ascites noted is recommended for fluid analysis/cytology to better assess the nature of the fluid present and to help rule out blood loss as a cause of anemia. While GI protein loss is the most likely differential, investigation into alternative etiologies is recommended. Consider liver function test and urinalysis with UPC after resolution of reported urinary tract infection. Liver biopsies should also be considered if surgery is elected.

Given the degree of anemia, a red blood cell transfusion is recommended prior to surgery. A clotting profile would also be recommended prior. If transfusion is elected, blood should be collected for pathology review prior to transfusion. Consider other diagnostics/therapeutics as clinical signs dictate.

Outcome/Further Testing:

Unfortunately, the owner elected for humane euthanasia due to financial constraints.

Necropsy: Post-mortem abdominal exploratory confirmed a splenic torsion, serous ascites, as well as cloth material within the stomach.

Image 4: Gastric foreign material.

Image 5: Splenic torsion.

Image 6: Right lateral radiograph.

Image 7: VD radiograph.

Discussion:

Multiple pathologies were discovered in this patient, most notably a gastric foreign body, primary splenic torsion (PST), and dilated lacteals consistent with protein-losing enteropathy. Notable clinical pathologies established prior to the ultrasound study included a marked anemia (15.9%), moderate leukocytosis (20.2 K), and severe hypoalbuminemia (1.5 g/dL). A positive saline agglutination test (SAT) was also noted. Bacteriuria (rods and cocci), hemoglobinuria, and mild pyuria (3 WBC/hpf) were also noted via SediVue Analyzer, but manual cytology was not reported. The interconnectivity of these pathologies will be discussed further here.

There are three broad categorical causes of anemia5:

1) Decreased production (anemia of chronic disease such as erythropoietin-related conditions or iron-deficiencies and bone marrow conditions)

2) Loss (hemorrhage)

3) Destruction (hemolysis, oxidative injury, parasitic, toxicity, etc.)

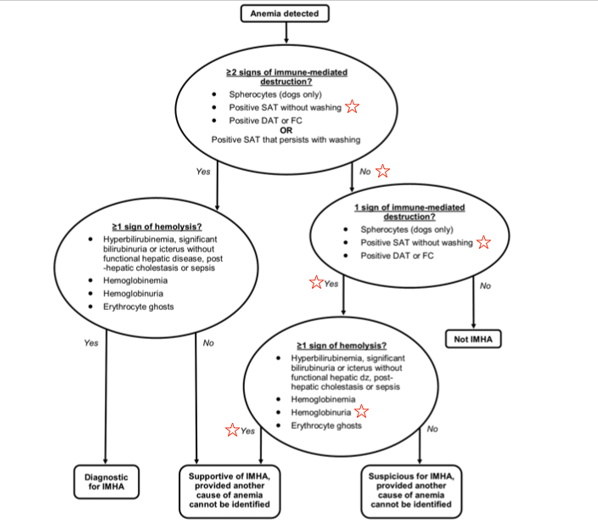

Further investigation would be necessary to fully elucidate the true etiology/etiologies, however, reasonable assumptions may be made to better understand the anemia. The initial concern for this patient’s anemia was presumed to be an immune-mediated disease (IMHA) due to the degree of anemia, positive saline agglutination test (SAT), and presence of hemoglobinuria. The mechanism of hemoglobinuria in PST dogs is suspected to be secondary to intravascular or intrasplenic (extravascular) hemolysis.2 Based on the ACVIM consensus statement on the diagnosis of immune-mediated hemolytic anemia, this patient would be classified as ‘supportive of IMHA, provided another cause of anemia cannot be identified.’1 [See Figure 1] However, a positive SAT can be a result of RBC rouleaux formation and rouleaux formation can be promoted in hypoalbuminemic patients.4 Further dilution and cytology would be necessary to differentiate between true agglutination versus rouleaux formation in light of a positive SAT. A CBC with pathology review would also be beneficial in this case to assess for regenerative changes, red blood cell morphologies, red blood cell pathogens, etc. to further strengthen the argument for a hemolytic cause of anemia. Given the exhaustive list of reported inciting causes of IMHA, this patient, coincidentally or not, has multiple listed morbidities associated with triggering IMHA (i.e. inflammatory disease, necrosis, urinary tract infection, etc.).

Figure 1: IMHA diagnostic algorithm as presented in the ACVIM consensus statement1

While an argument can be made for immune-mediated disease, when incorporating the physical exam findings into the assessment of the patient’s anemia, decreased production/chronic anemia could be considered the most likely, or most substantial, etiology. On physical exam, the patient was found to be alert and responsive, pale, cachectic with a BCS of 2/9 and MCS of 1/5, eupneic, with a normal heart rate of ~100 BPM, all suggesting chronic disease. In the face of an acute onset marked anemia (as commonly seen with IMHA), tachypnea, tachycardia, and associated mentation changes/weakness would be expected. An elevated bilirubin would also be suspected, especially given the degree of anemia. In the same light, RBC loss/hemorrhage would also be considered less likely (and largely ruled out in this case as the ascites on necropsy was grossly serous fluid and no evidence of hematochezia, melena, and only mild true hematuria [7 RBC/hpf]). Ultimately, the true cause of anemia is likely multifactorial in this patient.

Primary splenic torsion (PST) is rare and the etiology is poorly understood. Acute and chronic PST have been reported, and English Bulldogs are an over-represented breed, accounting for up to 11.8% of cases.3 Clinical signs associated with acute PST include abdominal pain and distention, vomiting, depression, and anorexia. Chronic PST presents with varying clinical signs including anorexia, weight loss, intermittent vomiting, abdominal distention, PU-PD, hemoglobinuria, and abdominal pain.3 It is difficult to determine the chronicity of the PST in this case. The owner reported a few day history of hyporexia, lethargy, and hematuria. Given the poor body and muscle condition, morbidities predating a few days are almost certain, however a chronic gastric foreign body and enteropathy (presumed PLE) may have predated and, in some theoretical manner, aided in a more acute onset PST. Given the over-representation of the breed, a genetic predisposition such as absent or weak gastrosplenic and/or phrenicosplenic ligaments may be a contributing factor.

Lack of reported historical vomiting and diarrhea makes assumptions of a chronic foreign body and PLE difficult. While diarrhea is the most commonly reported clinical sign associated with PLE, some studies show upwards of 33% of cases have no reported diarrhea.6 The marked hypoalbuminemia, along with the prominent mucosal changes noted, makes a PLE the most likely diagnosis for the cause of this patients hypoalbuminemia. GI biopsies would be necessary for a definitive diagnosis. Notable alternative etiologies such liver dysfunction, protein-losing nephropathies (PLN), malnutrition, and parasitism could also be considered. While the liver appeared subjectively decreased in size, aside from hypoalbuminemia, there were no direct or indirect hepatic markers on baseline labwork to suggest liver dysfunction (normal liver enzymes, cholesterol, bilirubin, globulins, and elevated glucose). Ultimately, liver function tests +/- biopsies would be necessary to rule out liver dysfunction as a cause of the hypoalbuminemia. A urine protein:creatinine ratio would also be indicated to assess for potential protein-losing nephropathies (PLN) following the resolution of the reported urinary tract infection. Fecal analysis and empirical deworming would also be indicated. All things considered, given the degree of weight loss, hypoalbuminemia, and mucosal changes, a chronic PLE would be the primary differential in this patient. Additionally, while uncommon to see both a diffuse enteropathy and gastric foreign material in the same patient, foreign body ingestion (pica) is not an uncommon manifestation of chronic GI disease in dogs.

Overall, this case presents an interesting constellation of clinical signs and pathologies that highlights the value and utility of ultrasound in veterinary practice.

References:

1. Garden OA, Kidd L, Mexas AM, Chang YM, Jeffery U, Blois SL, Fogle JE, MacNeill AL, Lubas G, Birkenheuer A, Buoncompagni S, Dandrieux JRS, Di Loria A, Fellman CL, Glanemann B, Goggs R, Granick JL, LeVine DN, Sharp CR, Smith-Carr S, Swann JW, Szladovits B. ACVIM consensus statement on the diagnosis of immune-mediated hemolytic anemia in dogs and cats. J Vet Intern Med. 2019 Mar;33(2):313-334. doi: 10.1111/jvim.15441. Epub 2019 Feb 26. PMID: 30806491; PMCID: PMC6430921.

2. Nelson, Richard W., and C. Guillermo Couto. “Chapter 86: Lymphadenopathy and Splenomegaly.” Small Animal Internal Medicine, Elsevier/Mosby, St. Louis, MO, 2014.

3. DeGroot W, Giuffrida MA, Rubin J, Runge JJ, Zide A, Mayhew PD, Culp WT, Mankin KT, Amsellem PM, Petrukovich B, Ringwood PB, Case JB, Singh A. Primary splenic torsion in dogs: 102 cases (1992-2014). J Am Vet Med Assoc. 2016 Mar 15;248(6):661-8. doi: 10.2460/javma.248.6.661. PMID: 26953920.

4. “Pattern Changes.” eClinpath, 18 Oct. 2016, eclinpath.com/hematology/morphologic-features/red-blood-cells/patterns/.

5. Thompson, Mark S. Small Animal Medical Differential Diagnosis (Third Edition). W B Saunders Company, 2018.

6. Simmerson SM, Armstrong PJ, Wünschmann A, Jessen CR, Crews LJ, Washabau RJ. Clinical features, intestinal histopathology, and outcome in protein-losing enteropathy in Yorkshire Terrier dogs. J Vet Intern Med. 2014 Mar-Apr;28(2):331-7. doi: 10.1111/jvim.12291. Epub 2014 Jan 27. PMID: 24467282; PMCID: PMC4857982.